From The

Cactulent: ADROMISCHUS HEMISPHAERICUS

Official

Bulletin of the London Cactus Club - October 1960 vol. 12 no. 6 p. 49-51

by Bryan Makin (Editor) [Other articles by BM on

this web site: White

Adromischus, A.

leucophyllus.]"Although I came across quite a

number of species of Adromischus growing

naturally in South Africa, the first one I

actually set out to find was that listed in the

local flora as A. rotundifolius. Since

then, I have learned that a complete range of

inter-grading forms exists along the west coast

of the Union, some of which have been given

specific names. But until the resultant mess has

been cleared up, I have chosen to stick to the

oldest relevant name, Adromischus

hemisphaericus, hence the apparent

contradiction between my opening remarks and the

title.

| A.

hemisphaericus can be found in a

small-leaved, rotund form on Signal Hill,

actually overlooking Cape Town itself,

and I have a nice pot-full in my present

collection. But, being ignorant of this

fact at the time, I chose the published

habitat of the Twelve Apostles [mountain

slopes] as the area for my search. I duly

left Cape Town by bus, travelling south

along the Cape Peninsula to the limit of

its local run, to the little coastal

village of Bakoven. This name is

pronounced BACK-OOF-N and its literal

translation is BAKE OVEN, so chosen

because of a peculiar hollow rock which

lies off shore shaped like the old Dutch

baking oven used by the early settlers. |

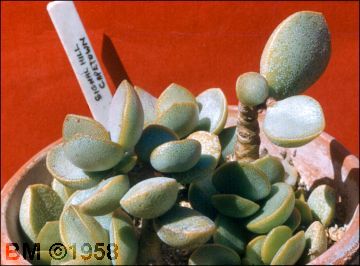

A. hemisphaericus

BM711, collected by H. Hall in 1958. |

In 1954, I

had started my outing directly after lunch and,

in the South African summer even on the coast,

the heat reflected up from the dry roadway at

this time of day can be very oppressive, and this

plus my recent meal, made me feel anything but

energetic. However, I turned my nose to the south

and continued along the roadway. The footpath

finished soon after leaving the bus. So, I had to

keep a wary eye and ear for traffic on the

twisting road. It unfailingly followed the

contour of the hills from which it had been cut

and fell away to the sea below on my left,

clothed in long trailing streamers of the giant

Mesemb, Carpobrotus edulis. The water

below was clear blue except where it lapped the

rocks. The door in the Oven was no longer visible

from where I stood. I looked around and the sandy

clay bank across the road rose sheer in parts for

ten, twelve, fifteen or more feet, but at others

showed possible footholds for an aspiring

ascendant.

Varying succulents

presented themselves at intervals, namely shrubby

Mesembs, occasional weedy-looking Crassulas, etc.

The most attractive was an Erepsia which was a

solid blaze of pink flowers and occurred

frequently along the roadside. My eyes were

constantly searching for succulents and

especially the Adromischus and suddenly I spotted

a plant on the edge of the vertical bank above

the road. Surely it was a Stapelia of some sort

and I cast about for a way up. It was a little

while before I found the plant again but, sure

enough, it was the well known S. variegata

to be precise, growing in short grass on the very

edge of the bank with its flower buds overhanging

the drop. None was open, but an investigation of

a large bud showed there was no doubt about its

identity. A few yards further along the road, I

found another S. variegata, on the other

side this time, growing deeply buried in almost

pure coarse sand in full sun! No sign of

Adromischus though and the sun was beginning to

weary me, so I turned and. retraced my steps,

having decided to explore higher up the lower

slopes of the Twelve Apostles range, as soon as I

could find a way up from the road.

These slopes were covered

in scrub bushes varying in height between one and

three feet with occasional clumps of the withered

leaves of bulbous plants that transform these

same hillsides into a pleasant colourful scene in

the beautiful Cape spring. But right now it was

the hot dry Cape summer and the only flowers were

those on the Erepsias and Carpobrotus, the latter

a pale straw yellow instead of the more

attractive magenta form. I scanned the slopes

somewhat forlornly now with the sun behind me

sinking lower into the western sky. A few

isolated boulders and rock outcrops gave a last

glimmer of hope and I picked my dusty way towards

each of them in turn. The first was bare and

unfruitful, but the second had a long crack

across the top overhung by a spreading bush. In

the shade of this bush and with its roots delving

into the crevice, was a beautiful blue mound of

that succulent composite, Kleinia repens.

How lovely it looked in its unblemished state

growing there on that hard granite-like rock of

Table Mountain Sandstone, but as I looked round

my exultation fell as I realised I had only a

couple of other rocks still to investigate. The

first was higher up the slope but seemed worth

the scramble since it was a sizeable boulder with

a few smaller rocks in attendance round it. I

finally stood before it and swept it with a

searching look. It had appeared grey and bare as

I approached, but now I could see a long sloping,

crevice some three or four feet in extent running

down the western face, and all along this crevice

were the thick stems and fleshy grey leaves of my

Adromischus. No opulent beauty this, no colourful

seeker after attention, but silvery-grey, scaly

leaves matching the colour of the rock itself and

asking for no-one's notice but that of the sun

and the rain in season.

In my album is a photograph

of that crevice with its Adromischus and in my

greenhouse is a pot with two labels. The newer

one reads "BM790 Adromischus

hemisphaericus", but the other says

"Adromischus rotundifolius,

collected Bakoven, Cape Peninsula, 1954".

The plant grows a little taller in cultivation,

up to about 5 in. and the leaves are less heavily

scaled and a bit larger than in the wild. They

vary according to age up to about 1 x 1½ in.

long, slightly concave on the front and rounded

on the back clothing the ascending stem. The

flower spikes rise in spring and open their

small, tubular blooms in mid-summer, the pale

"petals" being joined together and

fully recurved to clasp the tube. The species is

related to such other Adromischus as A.

bicolor, mammillaris, tricolor

and the recently named liebenbergii and fragilis.

| I have several

forms now, collected in different

localities, including one that becomes

almost white in the summer and another

that is covered in fewer scales but a

multitude of red spots. This latter came

from a place called Darling and makes a

very attractive plant. I have purposely

avoided all technicalities in this

account since the species and its

inter-grades are very much sub judice in

the taxonomic field. I would like however

to refer here to another plant so often

grown in collections as A.

hemisphaericus, but quite different

in appearance from the description I have

given. This is the low, squat, almost

stemless plant which is possibly the

commonest Adromischus in British

collections but which has thick, fleshy,

pointed leaves, much longer than broad,

tightly clustering and rarely, if ever,

blooming and certainly I have never seen

it in flower. In America, this used to be

known as "old mamillaria"

although not at all like the true A.

mammillaris. For years this plant

has remained an enigma, but it was

recently found again in the wild and has

been equated with A. vanderheydenii

n.n., which name I earnestly commend to

your attention. |

Possibly the spotted A.

hemisphaericus from Darling, BM655,

collected by H. Hall, plentiful on

granite outcrop. |

Finally, a

word on cultivation: A. hemisphaericus is

a very accommodating plant but does best with a

restricted diet and the maximum sunshine to

encourage the production of the silvery scales on

the otherwise green leaves. I like to grow mine

in an open cold frame in summer and find they

propagate easily from leaves."

|